Joseph Smith Reading With Rock in Hat

Two pictures:

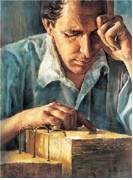

[To the left] The manner of translation was equally wonderful as the discovery. By putting his finger on one of the characters and imploring divine assist, then looking through the Urim and Thummim, he would see the import written in plain English on a screen placed before him. Afterwards delivering this to his emanuensi,[sic] he would again proceed in the same manner and obtain the meaning of the next character, and then on till he came to the office of the plates which were sealed up.1

[To the left] The manner of translation was equally wonderful as the discovery. By putting his finger on one of the characters and imploring divine assist, then looking through the Urim and Thummim, he would see the import written in plain English on a screen placed before him. Afterwards delivering this to his emanuensi,[sic] he would again proceed in the same manner and obtain the meaning of the next character, and then on till he came to the office of the plates which were sealed up.1

Truman Coe, Presbyterian Minister living among the Saints in Kirtland, 1836

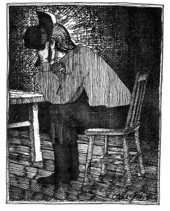

[To the right] I cheerfully certify that I was familiar with the manner of Joseph Smith'south translating the volume of Mormon. He translated the nearly of information technology at my Father'southward business firm. And I ofttimes sat by and saw and heard them translate and write for hours together. Joseph never had a drape drawn between him and his scribe while he was translating. He would place the director in his lid, and then identify his [face in his] hat, then equally to exclude the calorie-free, and and so [read] to his scribe the words equally they appeared before him.2

[To the right] I cheerfully certify that I was familiar with the manner of Joseph Smith'south translating the volume of Mormon. He translated the nearly of information technology at my Father'southward business firm. And I ofttimes sat by and saw and heard them translate and write for hours together. Joseph never had a drape drawn between him and his scribe while he was translating. He would place the director in his lid, and then identify his [face in his] hat, then equally to exclude the calorie-free, and and so [read] to his scribe the words equally they appeared before him.2

Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery, Oliver Cowdery's wife, 1870

These two descriptions of Joseph Smith translating the golden plates paint radically different pictures of the same effect. It easy to accept the finger-on-the-plates translation, but the rock-in-the-hat feels completely foreign. Yet, it is a much better attested description of the process than the kickoff.

Why do we take both of these pictures if the second amend fits the majority of descriptions? To answer that question, there are 2 stories that must be told: kickoff–why would anyone remember of translating with a rock in a hat?–and second–why nosotros are so surprised at that?

Why Exercise You Expect At Rocks in Your Lid?

When the English language left their villages and emigrated to the New World, they brought their customs and beliefs with them. Along with the hopeful, the adventurers, and the farmers,-—cunning men and wise women disembarked in the New World.3 To be a cunning man or a wise woman was to play a well divers and important office in pre-industrial villages. Keith Thomas, retired Professor of Modernistic History at Oxford University, wrote what has become the principle history of folk magic in England from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. He tells how, in the villages, contemporary medicine drove people to the cunning men and wise women who understood herbs. The lack of local police forces made the community depend on cunning folk to find lost or stolen goods.4 These hamlet specialists performed such important functions that Thomas notes that the community was "likely to believe that the cunning folk were taught by God, or that they were helped by angels, or fifty-fifty that they possessed some divinity of their ain. The common people, wrote Thomas Cooper, assumed that the ability of these wizards came by 'some extraordinary souvenir of God'."5

The cunning men and women exhibited their extraordinary talents in many means, but there is i that provides the backdrop against which immature Joseph Smith is more clearly divers. He belonged to a class of cunning men whose specialty was scrying, or seeing the hidden. It was a specialty with a very long and almost universal history.6 Anthropologist Andrew Lang, writing in 1905, describes the tools of their trade:

Not only is the plain crystal, or its congener the black stone, used, together with its first cousin the mirror, and the primitive substitute of water, merely almost whatsoever bright object seems to have been employed at one time or another. Thus we detect the sword among the Romans; and in mediaeval Europe polished fe . . . lamp-black is sometimes smeared on the mitt, or. . . a pool of ink poured into it; visions are seen in smoke and flame, in blackness boxes, in jugs, and on white paper. . . .7

All of these methods audio strange to our modern ears, but they were not but accepted just revered for near of man history. Past the time nosotros find scryers or seers in England between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, their tools were often stones and their functions had evolved into 2 full general forms; seeing a hidden hereafter, and seeing the hidden location of things that were lost (or the thief who fabricated them get "lost"). The conservative nature of such practices dictated that when the traditions of the cunning men and wise women are establish in the Palmyra expanse of the 1820s they still performed their traditional functions of telling fortunes and seeing things that were lost, hidden, or stolen.viii

Young Joseph Smith was a fellow member of a specialized sub-community with ties to these very erstwhile and very respected practices, though by the early 1800s they were respected but past a marginalized segment of order. He exhibited a talent parallel to others in similar communities. Even in Palmyra he was not unique. In D. Michael Quinn's words: "Until the Volume of Mormon thrust young Smith into prominence, Palmyra's virtually notable seer was Sally Hunt, who used a greenish-colored rock. William Stafford also had a seer stone, and Joshua Stafford had a 'peepstone which looked similar white marble and had a hole through the center.'"9 Richard Bushman adds Chauncy Hart, and an unnamed man in Susquehanna County, both of whom had stones with which they found lost objects.ten

There are some reminiscences that tell us how the village seers operated before modern history either forgot or dismissed them.. Lorenzo and Benjamin Saunders gave interviews in 1884 remembering their dealings with the Palmyra seer, Sally Chase. Lorenzo reported:

I tell yous when a human willme that anyone can get a rock, & see knowledge of futurity, I say that he is a liar & the truth is not in him. Steve Mungou lost his pocket book in the road with some $50 in coin in it. He went right to Sally Chase to get her to expect & see where it was; She went & looked. He was cartoon wood out of the woods. She said that pocket book lays correct at the side off a log in the woods where yous loaded that woods. It lays right at the side of the log well we went & hunted & raked the ground over where she said but could not find information technology. It past forth & finally one night got a paper from Canadagua [Canandaigua, New York], & in it was that a pocket volume was found & taken to an sometime Ontario Depository financial institution[.] Took it in that location & the owner could come & describe his book. And he went & found his pocket volume at the depository financial institution. I lost [a] drag tooth out of my drag, dragging on my brothers bounds there; I says: Sally, tell me where is that elevate tooth? She told me "it lays in a log heap." She says I think it lays a trivial past y'all volition notice it.

I went & hunted & hunted only could not find information technology there. I afterwards found information technology abroad over in one corner of the field.11

Benjamin provided a similar story: "My oldest Blood brother had some Cattle devious away. She claimed she could come across them just they were establish right in the opposite direction from where she said they were."12 These accounts portray the way Sally Chase functioned in the community. When things were lost, yous went to the seer who consulted her seer stone and described how to find the lost particular. The Saunders brothers could have been describing events from an English hamlet of over a hundred years earlier. In the cursory descriptions that accept survived, nosotros know that Lorenzo consulted her at least twice himself, one time to find the drag tooth and once to notice lost cattle. He besides tells united states of america of another client, Steve Mungou. Both brothers, however, found it necessary to append that, of course, Emerge was mistaken in the location she gave, a qualification that apparently didn't stop them from consulting her again.

Joseph Smith, long earlier golden plates complicated his position as a local seer, appears to take functioned just as Emerge Hunt did. Quinn reports that: "E. West. Vanderhoof [writing in 1905] remembered that his Dutch grandfather in one case paid Smith seventy-five cents to look into his 'whitish, glossy, and opaque' stone to locate a stolen mare. The grandfather soon 'recovered his creature, which Joe said was somewhere on the lake shore and [was] nigh to be run over to Canada.' Vanderhoof groused that 'anybody could have told him that, as it was invariably the way a horse thief would take to dispose of a stolen creature in those days.'"thirteen While Vanderhoof reported a positive event of the consultation, it is interesting that his statement includes a qualifier that has the same intent as those added by the Saunders' brothers. By the end of the century, i wouldn't want to actually credit a village seer when describing their activities. All the same, it isn't the effectiveness that is of import—information technology is the nature of the consultation. Sally Chase's clients consulted her to find things which were lost, and Joseph Smith had at least 1 customer who did the same.

The social expectations of the village seer also explain ii contradictory statements about what Joseph Smith did as a hamlet seer. The showtime argument comes from Henry Harris in 1833: "Joseph Smith, Jr. the pretended Prophet, used to pretend to tell fortunes; he had a stone which he used to put in his chapeau, past ways of which he professed to tell people'southward fortunes."fourteen Compare that statement to a story Lorenzo Saunders told to Edmund L. Kelley during his 1884 interview:

Nosotros went to Smiths one day, information technology was a rainy day; We went into the erstwhile mans shop, he was a cooper, and the one-time man had a shirt on it was the raggedest & dirtyest shirt, and all total of holes. & we got Jo. Smith to look & tell us what color our Girls hair was. well you see by & by some of them says become to Jo. says he Jo. come look into hereafter & tell us how it is in that location? Jo. says I tin can not do that, I can not wait into futurity I tin can non look into anything that is holy. The onetime man stood there and says: "I judge he can non await into my shirt so.15

Both Henry Harris and Lorenzo Saunders expected that Joseph Smith told fortunes. Of course they would take that expectation, considering everyone knew that was i of the typical functions of the seer. Still, where Harris may only be repeating the assumption, Saunders describes what happened when he asked Joseph to act on that assumption. At least in this case, Joseph refused. The fact that the joke in the account depends upon young Joseph's comment near non looking at that which is Holy and his father's holey shirt suggests that this was a remembered incident and that Joseph Smith, Jr. actually had refused. I suspect that the refusal tells us about the spheres in which Joseph believed that detail talent operated. That refusal suggests Joseph made a distinction between that which was holy (which I believe he classified as religion) and his other functions (which I believe he classified as a talent).

What the modern world tends to know about the hamlet seers is the upshot of only one of the means in which their talents were put to use. Since they could run into that which was subconscious, local seers became involved in the mania of digging for lost treasure. Every bit with the other functions of the cunning men and wise women, the idea of excavation for treasure traced its roots to England, including much of the accompanying lore. In England, the semi-scientific root of treasure seeking was the addiction of the wealthy burying their goods for prophylactic-keeping in the absenteeism of a deposit banking system.16 In the New World, the plausible explanation was based on the riches reputedly buried past Spaniards or pirates. It is likely that everyone could cite cases of people who had struck information technology rich through their digging, though none of them had, nor anyone they personally knew.17

In English tradition, seers were invited to assist the diggers in locating the buried goods. As Thomas explains: "In that location was not necessarily anything magical about the search for treasure as such, just in practice the assistance of a conjurer or wizard was very often invoked. This was partly because information technology was thought that special divining tools might help, such as the 'Mosaical Rods' for which many contemporary formulae survive."18

It is therefore no surprise that nosotros encounter the Palmyra seers engaged in the local mania for treasure excavation. As with the English do, still, it is important to note that money-digging didn't require the seer. They were but seen as useful. Note the relationship of the diggers to their guides in this series of descriptions Ronald Due west. Walker compiled:

The adepts often played a major role in money digging. The ii men who in 1827 sought neatly boxed Spanish dollars below the old pier at New London, Connecticut, were directed by an elderly wise woman. Seeking pirate treasure in Maine, three men imported from Connecticut, a "far-famed and wonderfully proficient rodsman" to assistance them. In turn, treasure-hungry farmers of Rose, New York, sought the help of a "medium," while the 1825 trek to the Susquehanna hills began with a "peeper" named Odle, whose power of "seeing undercover" piqued William Hale's involvement. Moreover, the longtime diggers around Bristol, Vermont, fabricated utilize of expert advice. They consulted a series of "prophets," including two women, an "old Frenchman" eastward of the mountains, and finally a conjuror who promised that by removing a few rocks and "shunning the solid ledge" the long-sought cave might be entered.nineteen

This places an important context around the all-time-known case of Joseph Smith, Junior'south participation in treasure-digging. Josiah Stowell, Sr., believed that he had found a lost Spanish silver mine and had his hired hands dig for information technology in 1825. When they were unable to find it, he hired Joseph Smith, Jr. to help them observe what they had dug for and missed.twenty This incident was the reason that in 1826, Stowell'south wife'due south nephew took Joseph to court as a "disorderly person," a term that was then defined in such a way that nosotros might consider it a case of fraud.21 Presumably, Peter Bridgeman believed that Joseph had defrauded his uncle because he used a seer stone. This would not be the terminal fourth dimension that Joseph's activities with a seer stone were described as fraud. In terms coined only later on, Joseph would be accused of being a "confidence man."22 One of Joseph Smith'south biographers, Dan Vogel, picks upward and continues this theme. As Vogel describes the reason why one might see Joseph as a con human being, he also provides the information that allows u.s.a. to come across the of import ways in which that label is a baloney of the actual historical situation:

A typical confidence scheme in Smith's time involved a transient who entered an area that was known for its tales of lost treasures and the charlatan'southward magical powers could be put to good reward. Using a "peep" rock or mineral rod, he would lead the credulous to a remote spot where he had previously deposited a few coins and was able to impress them by "finding" the coins. In the ensuing excitement, he would inquire to be paid for his services or, more than boldly, suggest that a company be established and that shares be sold. Thereupon, he would disappear with the money. On the other hand, he might string the people along by leading them to subsequent spots, so offer magical explanations for the failure to locate or secure the treasure. For example, he might tell them that the treasure was protected by an evil spirit or that they had not precisely followed the magical formula he had given them. Eventually he would propose that the undertaking be abased, whereupon he would slip out of town with the money.23

The implication is that since Joseph used a peep rock, he must be seen in the aforementioned category as those who ran a scam with i. Conspicuously the 1826 court appearance tells u.s. that some contemporaries considered him in that category. However, although the prove is circuitous, it appears that Joseph was acquitted of the charge at that time.24 Should he also be redeemed from the continuing charges?

Undoubtedly there were those who preyed upon the folk behavior of the too-trusting rural communities. Nevertheless, the fact that the communities would be willing to follow the conviction scheme simply tells u.s.a. that at that place was an existing belief system in which seer stones were considered effective and acceptable. The confidence men played off inherited traditions. However, the fact that there are quack pretenders in any profession does not propose that the unabridged profession is designed for dishonesty. Scams were run concerning seer stones not because seer stones were novel, but precisely because they were a traditional and respected method of finding that which was hidden.

There are two critical differences between the con men and the village seers. First, the charlatans were transients and the village seers were residential. The 2nd is that the con man elicited money for his talents, and the village seers were consulted. Nosotros have at least three descriptions of how Joseph related to his clients, including Josiah Stowell, and in each case the client came to him with their problem.25 The con men created the scam for coin and left so they would non have to bargain with the consequences. The true village seers were role of the community, and remained so through success and failure. Their clients came to them considering of a cumulative reputation. Against the records of a few scam artists we have the long tradition of village seers stretching back to England and covering hundreds of years of respectable service in their communities.

It is this traditional context of a finder of lost things, a come across-er of the unseen, that explains how rocks in the lid figure in to the story of Joseph Smith and the translation of the Book of Mormon. The plates were accompanied past the Nephite Interpreters, which were two stones prepare in a silver bow.26 These stones announced to have functioned in a fashion Joseph understood from his experience with a seer stone. Although he began translation with the Nephite Interpreters, the record indicates that he changed to using his own seer stone. Why put the rock in a lid to translate? That part of the flick is easy. That was how such a rock was used. For Joseph's community, that aspect was not unusual at all.27

Why translate with a stone? The conceptual link in Joseph's listen would have been that he had been able to run into that which was subconscious, and the meaning of the script on the plates was certainly hidden to understanding. Nevertheless, this wasn't a simple transition from seer to translator, even for Joseph. Joseph'due south talent was for the mundane, merely his gift was for the Holy. Joseph understood the difference between the 2 when Benjamin Saunders wanted him to meet into futurity. Joseph understood that when he was asked to translate, he was being asked to practice something very dissimilar from what village seers did. He was existence asked to do something very different from what learned men did (ii Ne. 27:15-18).

Joseph learned from his customs how to operate as a hamlet seer, but he didn't brainstorm to understand how to be God's seer until Moroni appeared to him. He did not fully make that transition until the sacred interpreters helped him move from finding lost objects to finding a lost people and lost gospel. Then, having learned to encounter that which was Holy, Joseph never returned to the mundane functions of the village seer. Eventually, he learned that he could use a seer rock only also as the Interpreters. Only when he learned to see that which was Holy could he translate–and and so information technology didn't matter the lens through which he saw.

It is at this point that some might wonder if I believe that all seers saw things in their seer stones. I believe that seers believed that that they saw things in their seer stones. Do I believe that the seer stone prepared Joseph to interpret?28 Just in that it allowed him to believe that he had a God-given talent that could be used for the purpose. Naught in the world view of the seers prepared him for translating. He didn't originally believe that his secular stones could translate, only the sacred interpreters. Even afterward when he learned that he could also translate through his ain seer stone, he consistently said that the translation was done through the gift and power of God, not through any kind of rock. He knew that no other village seer could do it; he knew that he could non practice information technology, save God alone intervened. Translating the plates was across the realm of the village seer and firmly and exclusively in the realm of God's Seer.

Why Are Nosotros Surprised that Joseph Used a Rock in His Hat to Translate?

If we can find a context in which Joseph translating with a seer rock makes sense, why practise we take to look and then hard to observe it? Why isn't it as natural for us as it was for Joseph? That story also requires that we delve into history; in this case, the history of the interconnections between what we understand to exist religion and what nosotros sympathise to be magic.

Judeo-Christian religion shared the cultural cradle of the aboriginal Middle East. Dr. Shawna Dolansky, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Northeastern Academy, notes: "Evidence from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia suggests that the dichotomy between magic and religion that is the starting bespeak for many discussions of magic past contemporary scholars was non necessarily evident in biblical times. The fact is, in these civilizations that were contemporary with biblical Israel, magic and faith were only get-go to be differentiated. Testify particularly from Mesopotamia shows that this dichotomy is not an inherent ane, but one that gradually develops over a menstruation of fourth dimension and is intimately tied to increasing social complexity."29

Many of the Old Testament stories that we accept as religion have much in common with magical practices. They are difficult to separate because their differentiation depended not upon the things that were done, but the manner those things were perceived. Sarah Iles Johnston, professor of Greek and Latin at Ohio State University explains:

The mod scholarly quest to establish a segmentation between magic and faith does have some roots in antiquity, insofar every bit both ancient and modern discussions hinge on terminology: what one chooses to call any particular activity (and, it follows, who is doing the choosing) determines whether the activity is understood as adequate or discredited, pious or cursing, religion or magic. In antiquity, magic (a term that I utilize as a shorthand style of referring to a variety of aboriginal Mediterranean words) almost always referred to someone else's religious practices; it was a term that distanced those practices from the norm–that is, from i'due south ain practices, which constituted religion.30

Stated simply, "what I exercise is religion, what you do is magic."31

Although it is difficult to see without close exam, the One-time Attestation exhibits this internal/external dichotomy between religion and magic. On the ane hand, information technology is conspicuously combative to people who perform certain acts. For example, nosotros find in Exodus 22:xviii the verse that underlay and then many later tragedies: "Thou shalt non suffer a witch to alive." Deuteronomy 18:10-12 provides a list of magical practices that should exist avoided: "There shall non be found amid you lot whatsoever one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer. For all that practice these things are an abomination unto the Lord."

In spite of these obvious prohibitions, Dolansky notes that when you examine the nature of the practices, information technology isn't the magic merely the magician that is the trouble. She concludes that "magic in the Hebrew Bible refers to the arbitration of divine power; and in the hands of priests and prophets information technology is perfectly legal."32 Information technology is not the act, just the actor that creates the separation between religion and magic.33 David Frankfurter, Professor of Religious Studies and History at the Academy of New Hampshire, notes that: "people in their own cultural systems utilize such descriptive labels for political, sectarian, or simply taxonomic reasons, fifty-fifty with little reality backside the labels. Practically whatever practice, that is, might be labeled 'magical' or 'sorcery' nether certain conditions."34

Because these terms and concepts were socially constructed, they played an important role when social relationships inverse. The division between religion and magic that affected Joseph Smith's world (and which is perpetuated in ours), followed the tremendous social disruption of the Protestant Reformation and the Historic period of Enlightenment. Every bit the Western world emerged from the Heart Ages, the Catholic Church had go the sole repository of answers to questions near how the world worked. As the Church had grown and conquered new territories, it frequently incorporated local religious practices into its ain doctrines and understandings. In detail, local concepts of sacred space and sacred ritual often retained their sacrality while nominally moving from pagan to Christian spheres.35 The Protestant Reformation inverse the definition of what was to be considered religion and what was accounted magic, and with that alter, triggered massive social realignments—first in England and afterwards in the Americas.

Where the Cosmic tradition had accepted all types of sacred identify and practice, the Reformation severely limited both. In redefining religion, it labeled as magic many of the aspects of Cosmic sacred space and ritual.36 Richard Bushman has noted that "The Enlightenment drained Christianity of its conventionalities in the miraculous, except for Bible miracles. Everything else was attributed to ignorant credulity."37 Notwithstanding, Jon Butler of the Department of History at Yale Academy points out:

By traditional accounts, magic and occultism died out in the eighteenth century: the rise of enlightenment philosophy, skepticism, and experimental scientific discipline, the spread of evangelical Christianity, the standing opposition from English Protestant denominations, the rise in literacy associated with Christian catechizing, and the cultural, economical, and political maturation of the colonies only destroyed the occult practice and belief of the previous century in both Europe and America. Yet meaning evidence suggests that the folklorization of magic occurred as much in America as in England. As in England, colonial magic and occultism did not so much disappear everywhere as they disappeared amidst certain social classes and became confined to poorer, more marginal segments of early American society.38

It is precisely this folklorization that created the social dichotomy in practices that were accepted past, in Butler's terms, the more marginal segments of early on American society. This separation with parallel persistence is what anthropologist Robert Redfield of the University of Chicago called a Lilliputian and Great Tradition. He explained:

Permit us begin with a recognition, long nowadays in discussions of civilizations, of the difference between a keen tradition and a little tradition. . . In a culture at that place is a keen tradition of the cogitating few, and there is a picayune tradition of the largely unreflective many. The great tradition is cultivated in schools or temples; the little tradition works itself out and keeps itself going in the lives of the unlettered in their hamlet communities. The tradition of the philosopher, theologian, and literary man is a tradition consciously cultivated and handed down; that of the fiddling people is for the well-nigh part taken for granted and non submitted to much scrutiny or considered refinement and improvement.39

Although some aspects of Redfield'southward separation of the traditions have been criticized,40 the basic idea of the two carve up but interrelated aspects of organized religion in a culture has peachy explanatory power. Irving Hexham, professor of Religion at the University of Calgary, describes the complex mod religious history of Korea in terms of the intertwining of a Little and Great Tradition:

When a Great Tradition is in decline its Little Tradition can keep with a vigorous religious life until another Swell Tradition seeks to impose its beliefs equally the religion of the people. This situation of religious change is well illustrated by the course of religious history in Korea, where the shamanism of the Silla kings was officially replaced by Buddhism. But with the pass up of Buddhism and the imposition of Confucian rituals by the Yi Dynasty shamanism once more emerged as the enduring Petty Tradition. Afterward in the nineteenth century when Confucianism declined, Christianity entered Korea and shamanism again reasserted its traditional role.41

It is this power to persist parallel to and intertwined with the Great Tradition that tells us how the social complex of the cunning men and wise women not only crossed the ocean from England, but formed a vibrant part of a divers segment of American order. The duality of traditions likewise explains the mutual antagonism between them. Every bit competing explanations of reality, the two are uneasy bedfellows at best and feuding relatives at worst. D. Michael Quinn noted this division in approaches to the Little and Great Traditions: "Early Americans who did non share the magic world view condemned such behavior and practices every bit irrational and anti-religious, simply intelligent and religious Americans who perceived reality from a magic view regarded such beliefs and practices as both rational and religious."42

Well-nigh by definition, we perceive history through the optics of the Peachy Tradition; the tradition with the greater social and economic standing and the tradition with greater ability to create a written legacy through the Enlightenment'southward association with education. The Corking Tradition writes the history that colors our perception of the Fiddling Tradition. In the case of what we call magic, the anti-magical opinion of the Groovy Tradition makes the folk magic Little Tradition an embarrassment. Andrew Lang, a British anthropologist of the last generation, provides a fascinating example of what happens when the Neat Tradition expectation meets the Little Tradition reality: "'I am glad to say my people are non superstitious,' said a worthy Welsh clergyman to a friend of mine, a practiced folklorist, now, alas, no more, and went on to explain that there were no ghosts in the parish. His joy was damped, it is true, one-half-an-hour later, when his invitee inquired of the school children which of them could tell him where a bwggan was to be seen, and found at that place was not a kid in the school but could put him on the track of ane."43

The disdain of the Great Tradition for the Footling Tradition is axiomatic in an business relationship of a trial for fraud, held in Kent, England, in 1850: "The accused, who had the appearance of an agronomical labourer, resided at Rolvenden, where he enjoyed the reputation of being 'a cunning homo', able to cure diseases, to explain dreams, to foretell events, to tell fortunes, and to recover lost property. He was resorted to as a magician by the people of miles effectually, principally by the ignorant, simply too by parties who might accept been expected to know amend."44 The facts of the instance are that many in the community consulted this cunning man. Of class, they had to accept been ignorant folk. Nevertheless, there were some who didn't announced and then ignorant, although even they–should have known better.

Alan Taylor, a beau at the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, and an assistant professor at the College of William and Mary, explains the chasm between the Great and Trivial Tradition by focusing on Martin Harris:

[Martin Harris] was an honest, hard-working, acute homo honored past his townsmen with substantial posts as fence-viewer and overseer of highways just never with the most prestigious offices: selectman, moderator, or assemblyman. In the previous generation in rural towns like Palmyra substantial farmers like Harris would have reaped the highest status and most prestigious offices. But Harris lived in the midst of explosive cultural change as the capitalist market and its social relationships rode improved internal transportation into the most remote corners of the American countryside. The agents of that alter were the newly arrived lawyers, printers, merchants, and respectable ministers who amassed in villages and formed a new elite committed to "improving" their towns and their humbler neighbors. The village elites belonged to a new self-conscious "middle course," simultaneously committed to commercial expansion and moral reform. Because of their superior contacts with and cognition of the wider world, the new village elites reaped higher standing and prestigious posts from their awed neighbors.

Utterly self-confident in their superior rationality and access to urban ideas, the village elites disdained rural folk notions every bit ignorant, if not vicious, superstitions that obstructed commercial and moral "improvement." Through ridicule and denunciation, the village middle grade aggressively adept a sort of cultural imperialism that challenged the folk beliefs held by farmers like Martin Harris. Harris's fabric prosperity was comparable to the village aristocracy's but, because of his hard physical labor and express education, culturally he shared more with hardscrabble families like the Smiths. A hamlet lawyer needed only scan Harris's gray homespun attire and large strong hat to conclude that a farmer had come to town.45

We should not expect that because the Little Tradition is associated with the less educated that they were therefore simple or naÔve. Martin Harris might have been a participant and believer in the Little Tradition, but that doesn't mean that he threw caution to the current of air. The new elite might have seen Martin Harris as an ignorant and credulous farmer, only he would have seen himself as a cautious believer. His credulity immune for true seers, merely his caution told him that there were charlatans abroad. He pointedly told Joseph: "I said, Joseph, you know my doctrine, that cursed is every one that putteth his trust in homo, and maketh flesh his arm; and we know that the devil is to have swell power in the latter days to deceive if possible the very elect; and I don't know that you are i of the elect. Now y'all must not blame me for not taking your word."46

To resolve his question of whether or non he should support the Book of Mormon, Martin tested Joseph. When a pin Martin was using to pick his teeth fell into straw around his anxiety, he outset attempted to find it. Not succeeding, he asked Joseph to apply his seer stone to find the pin. Joseph did, bolstering Martin's confidence that Joseph had the talent he professed.47 I find it particularly apt that the nature of the test was to find something lost. That is, of grade, what a seer did.

Nevertheless, believing in Joseph every bit a true prophet and true seer had Martin straddling two traditions. The hamlet seer belonged to the Little Tradition and a true prophet belonged the Great Tradition. Those in the Little Tradition understood that their quotidian practices were not religion (though they certainly didn't consider them un-Christian). They fifty-fifty understood that their hamlet practices were not respected by the Great Tradition. This is the reason that so many of those who participated in the Niggling Tradition attempted to separate themselves from information technology when they were later part of the Nifty Tradition, or when an interviewer from the Smashing Tradition asked virtually the old days. Richard Bushman demonstrates how this pressure affected the reminiscences of some of Joseph Smith's neighbors:

The forces of eighteenth-century rationalism were never quite powerful enough to suppress the belief in supernatural powers aiding and opposing human enterprise. The educated representatives of enlightened idea, newspaper editors and ministers particularly, scoffed at the superstitions of mutual people without completely purging them. The scorn of the polite world put the Palmyra and Manchester money diggers in a dilemma. They dared non openly describe their resort to magic for fearfulness of ridicule from the fashionably educated, and nonetheless they could not overcome their fascination with the lore that seeped through to them from the past. Their embarrassment shows in the affidavits Hurlbut collected. William Stafford, who admitted participation in 2 "nocturnal excursions," claimed he idea the thought visionary all along, but "being prompted by curiosity, I at length accepted of their invitations." Peter Ingersoll made much more elaborate excuses. 1 time he went along became information technology was lunchtime, his oxen were eating, and he was at leisure. Secretly, though he claimed to be laughing upward his sleeve: "This was rare sport for me."48

Not merely does understanding the Neat and Little Traditions explain the antagonism we see in the Peachy Tradition histories, but the dual traditions too help explicate one of the features or a Little Tradition religion when it is transformed into a Cracking Tradition religion. That shift in social credence and expectation triggers a responsive shift in the way the new religion sees itself and its history.

Morton Smith, a professor of History at Columbia University, examined this tendency in early Christianity, which began equally a Piffling Tradition organized religion, but became a Groovy Tradition religion. Smith notes that the earliest forms of Christianity had a strong analogousness with magical practices—practices that remain in descriptions of the healing miracles and turning water to wine. By the time of the gospels, however, that history was existence written to remove references to magic. He concludes:

What evidence did the Christian tradition, equally presented in the gospels, have in common with the picture of Jesus the sorcerer? Since the authors of the gospels wished to defend Jesus against the accuse of magic, we should expect them to minimize those elements of the tradition that ancient opinion. . . would accept to be evidence for information technology, and to maximize those that could be used against it.

This expectation is, in the primary, confirmed. The evangelists could not eliminate Jesus' miracles because those were essential to their case, just John cut downwards the number of them, and Matthew and Luke got rid of the traces of physical means that Marker had incautiously preserved.49

The New Testament presented its message to, and participated in, a Great Tradition that Morton Smith notes was: "hostile to magic."50 So too did the mod Saints tell their story within and to a Slap-up Tradition that was hostile to magic.

Every bit the early saints transitioned from a collection of believers into a formal religion, they began to encounter themselves within the Neat Tradition. Every bit with early Christianity, the stories they told of themselves naturally were recast to altitude themselves from their Little Tradition heritage and provide an adequate Great Tradition history. One of the obvious places to see this process in activeness is with the tools of the translation. We all know that Joseph used the Urim and Thummim to translate the Book of Mormon—except he didn't. The Volume of Mormon mentions interpreters, merely non the Urim and Thummim. It was the Volume of Mormon interpreters which were given to Joseph with the plates. When Moroni took back the interpreters after the loss of the 116 manuscript pages, Joseph completed the translation with one of his seer stones. Until subsequently the translation of the Book of Mormon, the Urim and Thummim belonged to the Bible and the Bible only.51 The Urim and Thummim became office of the story when it was presented within and to the Swell Tradition. Somewhen, even Joseph Smith used Urim and Thummim indiscriminately equally labels generically representing either the Book of Mormon interpreters or the seer stone used during translation.52

The Urim and Thummim were traditionally divinatory rocks, simply almost importantly, they were biblically adequate divinatory rocks.53 From the Great Tradition perspective, their presence in the Bible made them religion, not magic. I suspect that the 2 interpreters made a natural comparison to the two stones, one Urim and one Thummim, from the Bible. Calling the biblical divinatory tools "rocks" instead of Urim and Thummim seems to demean them. The reverse process, calling the interpreters and seer stones Urim and Thummim, places them in a more appropriate religious category where they belong because of the sacred use to which they were put in translating the Book of Mormon.

This recasting of history was a story the Saints told themselves equally much every bit what they presented to the world. I doubt that there was any conscious attempt to reconcile their history with Bang-up Tradition expectations, let solitary any attempt at deception. Information technology was simply the natural response to their self-definition as a religion rather than a folk belief. It was a story told in a way that they subliminally knew was advisable for a Great Tradition religion. The new history did non deny the by or alter the facts, but recolored them with a new vocabulary.54

Why, then, are we and so surprised to learn that Joseph translated with a rock in his hat? That is a Trivial Tradition clarification and we are now firmly in the Great Tradition. We share the Great Tradition contempt to those elements of the Petty Tradition. Time has made the gap even greater than it was in Joseph'south 24-hour interval. Why practise nosotros take the ii pictures with which we began? The more than authentic, just more than uncomfortable picture is a Little Tradition image. The other is a Great Tradition paradigm. We have both because we tin tell the story from two different perspectives.

Regardless of the perspective from which nosotros tell the story, the essential fact of the translation is unchanged. How was the Book of Mormon translated? Every bit Joseph continually insisted, the only real respond, from any perspective, is that it was translated by the gift and power of God.

Notes

1 Truman Coe to Mr. Editor, Hudson Ohio Observer, August 11, 1836 cited in Dan Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 1:47.

2 Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery, "Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery Affidavit, fifteen February 1870," in Early on Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Salt Lake Metropolis, UT: Signature Books, 1870), 5:260.

3 Catherine 50. Albanese, A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 68. Also Jon Butler, Brimful in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Academy Press, 1992), 67.

4 Keith Thomas, Religion and the Refuse of Magic (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971), 649-l.

5 Ibid., 266.

6 Deanna J. Conway, Crystal Enchantments: A Complete Guide to Stones and Their Magical Properties (Berkeley. Calif.: The Crossing Press, 1999), 291-iii.

7 Andrew Lang, Crystal Gazing: Its History and Practise, with a Word of the Evidence for Telepathic Scrying (New York: Dodge Publishing Company, 1905), 32.

8 For the practices, come across Thomas, Religion and the Reject of Magic, 656. Herbert Passin and John Westward. Bennett, "Changing Agronomical Magic in Southern Illinois: A Systematic Analysis of Folk-Urban Transition," (reprint of a 1943 article) in The Study of Folklore, edited by Alan Dunces (Englewood Cliffs, New Bailiwick of jersey, 1965), 316-17, talk over agronomical magic in an Illinois town as nerveless in 1939, when the practices were beginning to fade. They note that they were practices that followed the Old English pattern.

9 D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (Common salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), 38.

10 Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Ancestry of Mormonism (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Printing, 1984), lxx.

11 Lorenzo Saunders, "Lorenzo Saunders Interview, 12 November 1884," in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1884), 2:154-55.

12 Benjamin Saunders, "Benjamin Saunders Interview, Circa September 1884," in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Salt Lake Urban center, UT: Signature Books, 1884), ii:139.

thirteen Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, 39.

fourteen Henry Harris, "Henry Harris Statement, Circa 1833," in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, five vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1833), 2:75.

15 Lorenzo Saunders, interviewed by E. 50 Kelley, 12 Nov 1884, "Miscellany," E. L. Kelley Papers, RLDS Church Library-Athenaeum, Independence, Missouri, p. xi, in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Salt Lake Urban center, UT: Signature Books, 1833), 2:155.

xvi Keith Thomas, Organized religion and the Pass up of Magic, 234.

17 Ronald W. Walker, "The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Digging," BYU Studies, 24, no. 4 (Fall 1984):433, notes: "The reality of actual treasure finds hardly explains the power and tenacity of the reassure myth "Finds' were never commensurate with actual earthworks and were more a matter of accidental discovery than conscious magical enterprise. Even the discovery of mines, allegedly the most successful of the diggers' pursuits, evoked skepticism and lacked documented results."

18 Thomas, Organized religion and the Decline of Magic, 236.

xix Walker, "The Persisting Idea of American Treasure Hunting," 439-forty.

20 Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 48.

21 Bruce A. Van Orden, "Joseph Smith's Developmental Years, 1823-29 (JS ñ H 50-67)," In Studies in Scripture, Vol. ii: The Pearl of Slap-up Toll, edited by Robert L. Millet and Kent P. Jackson, (Salt Lake City: Randall Book, 1985),373.

22 Dale R. Broadhurst, "Joseph Smith: Nineteenth Century Con Man?" accessed July 2009 from http://sidneyrigdon.com/criddle/Smith-ConMan.htm, provides a long and nicely documented piece that clearly argues that Joseph Smith was precisely a con man, and was described every bit 1. That he would accept been seen as a con human being by the writers from the Bully Tradition is certainly understandable (see later in this newspaper). Even so, seem from within his own social and economic class, the term is unwarranted and inaccurate. It is a historically authentic misrepresentation, simply a misrepresentation nonetheless.

23 Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet, xiv.

24 Previous records of what happened at the hearing accept been supplemented by the discovery of court documents that accept allowed a more complete legal analysis of the conclusions. The discussion of what happened at this hearing is beyond the scope of this papers. Sources to be consulted are: Marvin S. Hill, "Joseph Smith and the 1826 Trial: New Evidence and New Difficulties," BYU Studies 12, no. ii (1972):223-33, Gordon A. Madsen, "Joseph Smith'southward 1826 Trial: The Legal Setting," BYU Studies thirty, no. ii (1990):91-108, "Just the Facts: The 1826 Trial (Hearing) of Joseph Smith," Accessed July 2009 from http://www.lightplanet.com/response/1826Trial/facts.html.

25 Vanderhoof's gramps came to Joseph to ask about the lost mare. Josiah Stowell came to Joseph to hire him to assistance find the silver mine. Martin Harris asks Joseph to find the pin he dropped in the straw (discussed below).

26 J. Westward. Peterson, "William Smith Interview with J W. Peterson and W. S.Pender, 1890," in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 Vols., vol. 1 (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 09/03/23 1890), 508. A. W. Benton, "Mormonites," Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate 2:15 (Apr ix, 1840), 201, as quoted in Stephen D. Ricks, Joseph Smith's Means and Methods of Translating the Volume of Mormon (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Inquiry and Mormon Studies, 1986), 3.

27 "Palmyra Reflector, ane February 1831," in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols., (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books), two:243, "'Peep stones' or pebbles, taken promiscuously from the brook or field, were placed in a hat or other state of affairs excluded from calorie-free, when some wizzard or witch (for these performances were not confined to either sexual activity) applied their eyes, and nearly starting [staring?] their [center] balls from their sockets, declared they saw all the wonders of nature, including of form, ample stores of argent and aureate." Bracketed text retained from Vogel.

28 Marking Ashurst-McGee appears to run into a developmental path from Joseph'southward apply of folk magic into his abilities as a prophet. Clearly at that place is a connection, but I seem to see a greater separation than he does. Mark Ashurst-McGee, A Pathway To Prophethood: Joseph Smith Junior As Rodsman, Village Seer, And Judeo-Christian Prophet, Master'southward Thesis (Logan, Utah: Utah State University, 2000), iii, "For the nigh part, I present Joseph Smith'south divinatory evolution as he himself experienced it. Dowsing with a rod, seeing things in stones, and receiving heavenly revelations were as existent to Smith as harvesting wheat. In guild to sympathise his progression from rodsman to seer to prophet, i must first sympathise his worldview. The mental universe of early American water witches and village seers forms ane of the historical and cultural contexts in which Joseph Smith adult his divinatory abilities." Reacting specifically to this argument, my objection would be that Joseph Smith did non "develop his divinatory abilities," simply rather that they were bestowed upon him a s a gift from God, leveraging a talent he already had into the confidence to do what otherwise he would never have believed he could take washed.

Alan Taylor likewise indicates a developmental path: Taylor, "Rediscovering the Context of Joseph Smith's Treasure Seeking," 21, "Indeed, I would contend that Joseph Smith, Jr.'s transition from treasure-seeker to Mormon prophet was natural, like shooting fish in a barrel, and incremental and that information technology resulted from the dynamic interaction of two simultaneous struggles: kickoff, of seekers grappling with supernatural beings after midnight in the hillsides, and, 2nd, of seekers grappling with hostile rationalists in the hamlet streets during the solar day." Although these factors certainly contributed to the development of Joseph Smith the person, I do non see them as foundational for Joseph the Prophet. I come across Moroni's visit as creating a primal shift in his worldview, requiring that he relearn his place and reassign his talent to the Lord. It may not take been world-wrenching, but it yet was dramatically different from the context of his daily life prior to that event.

29 Shawna Dolansky, At present You Meet Information technology, Now Yous Don't: Biblical Perspectives on the Human relationship Between Magic and Faith (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2008), 21.

thirty Sarah Iles Johnston, "Magic," in Religions of the Ancient Earth: A Guide, ed. Sarah Iles Johnston (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004), 140. Dolansky, Now You lot Run into It, Now You Don't, xv, "In the instance of the ancient earth, information technology is hard to observe firm divisions between magical and religious activities until the time of classical Hellenic republic, and then those categories refer to social rather than substantive distinctions."

31 Dolansky, Now Yous See It, Now You Don't, 4: "The problem of differentiating between actions that are magical and those that are religious is important in the fields of anthropology and religious studies. Both magic and religion claim access to realms outside of ordinary reality and attempt to manipulate supernatural forces for desired outcomes in the natural earth. Scholars have approached the categories of magic and organized religion from a diversity of perspectives, distinguishing them on the ground of their techniques, social effects, and the status of their principal proponents. Some have suggested that there is no real difference, that the categories only denote social conventions ("what I do is faith, what you exercise is magic") and that the terms themselves should be dissolved altogether.

"The problem of defining magic has been a major portion of most LDS responses to the accusation that Joseph Smith participates in magic or the occult. In all cases, the problem is not with the facts, but with the connotations of the labels. Meet the following discussions of the utilize of the term "magic," and to what it might use: John Gee, "Alchemy, Isaac and Jacob," A review of "The Use of Egyptian Magical Papyri to Authenticate the Book of Abraham: A Disquisitional Review" by Edward H. Ashment, FARMS Review, 7, no. 1, (1995): 47-67, John Gee, "Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, revised and enlarged edition," A review of "Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, revised and enlarged edition" by D. Michael Quinn, FARMS Review, 12, no. 2, (2000):two-six, William J. Hamblin, "That Quondam Black Magic," A review of "Early Mormonism and the Magic Earth View, revised and enlarged edition" by D. Michael Quinn, FARMS Review, : 12,no. ii (2000 ): 3-nine, Rhett Due south. James, "Writing History Must Non Be an Act of 'Magic,'" A review of "Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, revised and enlarged edition" by D. Michael Quinn, FARMS Review, 12, no. 2 (2000):2-4.

32Dolansky, Now You See It, Now You Don't, 99.

33 Ibid., 99-100.

34 David Frankfurter, "Dynamics of Ritual Expertise in Antiquity and Beyond: Towards a New Taxonomy of "Magicians"," in Magic and Ritual in the Ancient Globe, ed. Paul Mirecki and Marvin Meyer (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2001), 159.

35 Karen Louise Jolly, "Magic, Miracle, and Popular Practise in the Early Medieval West: Anglo-Saxon England," in Religion, Science, and Magic: In Concert and in Conflict, ed. Jacob Neusner, Ernest S. Fredrichs and Paul Virgil McCracken Flesher (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 176, "Although there was conflict in early on medieval society between the extremes of magic and organized religion–a production of the Christianizing process in which the converted and the church hierarchy redefined the acceptable and unacceptable–there were also gray areas of assimilation in which practices stemming from a similar outlook were transformed into something adequate. The Christian Church, though openly countering magic with miracle, was non blind to this assimilation procedure as another ways of conversion.

"The extremes of magic and religion or scientific discipline, although well defined in most cultures, would necessarily have such greyness areas between them, a product of the influences of modify over time, as the adequate and the unacceptable were redefined."

36 Keith Thomas, Religion and the Reject of Magic, chapter three, "The Impact of the Reformation," provides extensive examples of the style in which this procedure moved through the Protestant rejection of Roman Catholicism. He concludes (75-76): "Protestantism thus presented itself as a deliberate effort to take the magical elements out of organized religion, to eliminate the idea that the rituals of the church had almost them a mechanical efficacy, and to abandon the try to endow concrete objects with supernatural qualities past special formulae of induction and exorcism."

37 Richard 50. Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, vii.

38 Butler, Brimful in a Sea of Religion, 83

39 Robert Redfield, The Little Community and Peasant Gild and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960, rpt 1989.), 41-42.

twoscore Edith Badone, "Introduction," in Religious Orthodoxy and Popular Organized religion in European Lodge, ed. Edith Badone (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 6: "Redfield's piece of work is in the tradition of the "ii-tiered" models of religion that Brown seeks to escape. Like the term pop organized religion itself, the great tradition-piffling tradition distinction has helped to perpetuate the misconception that popular religion is always rural, primitive, unreflective, and traditional, as opposed to the urban, civilized, intellectual, and modern religion of the aristocracy." Stanley Brandes, "Determination: Reflections on the Report of Religious Orthodoxy and Pop Organized religion in Europe," in Religious Orthodoxy and Popular Faith in European Gild, ed. Edith Badone (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 187: "Despite these theoretical advances, Redfield and his followers–similar the evolutionists earlier them–implicitly denigrated the organized religion of the masses. Not only did they view popular religion equally less reflective and creative–in other words, more than reactive–than that of the elite but they also believed that popular religion lagged backside elite faith temporally; aristocracy beliefs and practices of one century might be discovered amidst the peasantry of the next."

41 Irving Hexham, "Modernity or Reaction in Due south Africa: The Case of Afrikaner Faith," in Modernity and Religion: Papers Presented at the Consultation on Modernity and Faith Held at the University of British Columbia, December. 15-eighteen, 1981, ed. William Nicholls (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1988), 81.

42 Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, 225.

43 Lang, Crystal Gazing, 1.

44 David Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750-1914, Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture, ed. Peter Burke and Ruth Finnegan, vol. 19 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 172.

45 Alan Taylor, "Rediscovering the Context of Joseph Smith'south Treasure Seeking," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 19, no. four (Winter 1986):21. Internal references silently removed.

46 Martin Harris interview with Joel Tiffany, Tiffany'due south Monthly, V , 169.

47 Ibid., 164.

48 Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, 71-72.

49 Morton Smith, Jesus the Magician (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1978), 92.

50 Ibid., 146. As might be expected, Morton Smith'due south presentation of Jesus equally a magician is even more controversial than calling Joseph Smith a magician. John Gee, "'An Obstruction to Deeper Understanding'." Review of D. Michael Quinn, Early on Mormonism and the Magic Globe View, revised and enlarged edition, in FARMS Review of Books, 12 no. 2 (2000):188 notes that Morton Smith'due south idea that there were itinerant Greek magicians has been discredited. Gee does annotation (p. 186), "If Jesus can exist seen in such a context [equally a magician], why non Joseph Smith?"

51 J. V. Coombs, Religious Delusions: Studies of the False Faiths of To-Mean solar day (Cincinnati: The Standard Publishing Visitor, 1904), 61-62, "Dr. Wyl says that the proper name Urim and Thummim was first used by West. Due west. Phelps about the fourth dimension of the publication of the Volume of Commandments. This is 10 years afterward Moroni'due south visit. In the interim the work of translating is done by seer stones and rock spectacles! What a blessed affair information technology is that the more dignified instrument came soon plenty to get into the second edition of the revelations, at the aforementioned time belated Moroni makes his advent!"

52 Richard Van Wagoner and Steve Walker, "Joseph Smith: 'The Gift of Seeing'", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Idea vol. 15, no. 2 (Summer 1982):62, "These stones could not accept been the Nephite interpreters, yet Joseph specifically calls them 'Urim and Thummim.' The most obvious explanation for such wording is that he used the term generically to include any device with the potential for 'communicating light perfectly, and intelligence perfectly, through a principle that God has ordained for that purpose,' as John Taylor would later put it." See besides Mark Ashurst-McGee, "Moroni as Angel and as Treasure Guardian," FARMS Review 18, no. 1 (2006):42.

53 This is an intentional distillation of the tradition, which would never have accepted the crude designation of "rocks" for the tradition stones the Urim and Thummim represented. There is a long tradition that they were associated with the gems on the ephod. See Cornelis Van Dam, The Urim and Thummim: A Means of Revelation in Ancient Israel (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbruans, 1997), 16-23, 27-31.

54 The saints themselves would not have perceived a swell partition in their participation in the two cultural spheres. For them, the transition was probable imperceptible, even though they began to see themselves from the perspective of the religion they had joined. Pecker Hamblin notes that they never did label themselves with any of the terms that the Great Tradition would have used to draw their Fiddling Tradition practices. William J. Hamblin, "That Onetime Black Magic," Review of D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, revised and enlarged edition, in FARMS Review of Books 12 no. 2 (2000): 233, makes this indicate in reference to Quinn'due south association of the terms with Joseph Smith and his peers: "Joseph Smith never called himself a magician, magician, occultist, mystic, alchemist, kabbalist, necromancer, or wizard. He did non 'embrace' this 'self-definition.' Nor did whatever of his followers."

Source: https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august-2009/joseph-the-seer-or-why-did-he-translate-with-a-rock-in-his-hat

Posting Komentar untuk "Joseph Smith Reading With Rock in Hat"